A last will and testament, also called a “last will,” is a legal document describing how an individual wishes for their property to be distributed after they die.

Estate can comprise real estate, personal property, insurance benefits, and more. The testator may designate beneficiaries of their estate during their lifetime, whether they are blood relatives (such as children, siblings, parents, or adopted children) or not (such as coworkers or charitable organisations).

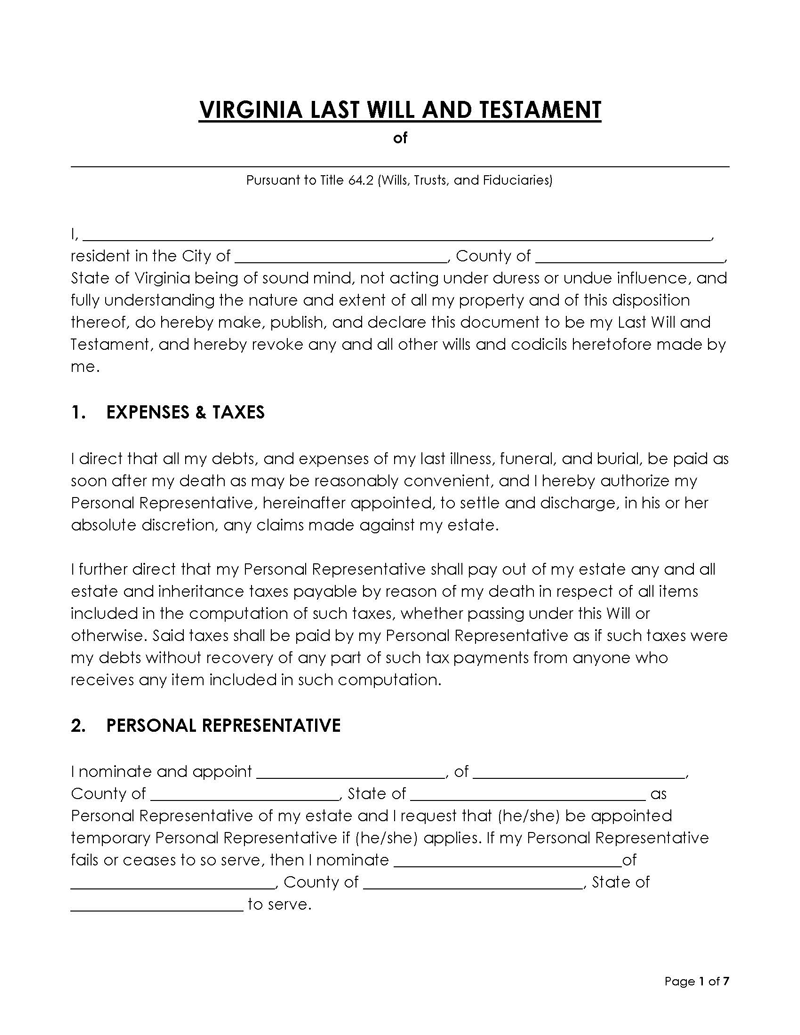

In the United States, an individual’s last will and testament is the document created by the individual that outlines who they want to inherit their estate after their death. The person writing the will is called the “testator.” If a person is at least 18 years old and has the mental capacity to execute the document, they can write a last will. The last will in Virginia establishes how the testator’s property is divided after they pass away.

A will must be properly executed in accordance with Virginia state law in order to be considered valid. Wills in Virginia are used as estate planning documents. Any codicil or amendment that the testator or another person adds at the testator’s request should also be followed when executing the will.

The most important parts of a will are the testator’s intentions regarding who should inherit the estate and how the property is to be divided. The successful execution of a will is determined by adhering to state laws.

Free Template

Why Do You Need a Last Will and Testament in Virginia

It is not mandatory for residents of Virginia to have a last will and testament. However, making a last will for your Virginia property ensures that your assets are distributed according to your wishes. This avoids the probate process and intestacy rules, which can be time-consuming and costly for the beneficiaries.

The main justification for making a will in Virginia is to ensure that your wishes, not those of the court, are followed when dividing your estate. Intestacy laws are based on standard inheritance rules that frequently conflict with your wishes. A last will and testament can help to prevent this. It will protect surviving family members who may have concerns about the distribution of property left behind.

Such a last will also allow you to name a guardian for any minor children you may leave behind. Additionally, you can appoint a manager of your estate to act on the minor’s behalf since minors cannot manage estates until they are 18 years old. This last will can also be used to create a pet trust for your pet(s).

In Virginia, through a will, you can also name an executor, who is a party appointed to ensure the last will and testament is followed after your death. This means the court does not have to supervise the distribution process as long as the last will is legally enforceable.

If a will is not created, your property would be subject to intestacy laws, which are laws that make the state in charge of the distribution of the estate of the deceased. This can result in the property being distributed to undeserving recipients or against your wishes.

Virginia’s intestacy laws distribute property in the following order of priority: close relatives (spouse and children, parents, grandchildren, siblings), then distant relatives (grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces and nephews, and so on). The laws aim to find the closest living relatives until the list is exhausted. If none is found, the property is given to the state. The entire intestacy process can be costly for the beneficiaries and can take years due to a lengthy legal process.

How to Make a Last Will and Testament in Virginia

States typically codify their laws regarding wills in their constitutions or general statutes, defining what constitutes a valid will and providing the rules for executing a will. The following steps can be followed to create legally valid wills in Virginia:

Step 1: Check eligibility

The first step is checking whether the property to be put in the will is eligible for inheritance. Non-probate assets are property that passes to beneficiaries without a probate process. Property held in joint tenancy passes to the other joint tenant upon death and is not subject to probate in Virginia, according to state law. Other assets, such as life insurance policies, pension plans, paychecks, and similar instruments, can be included in the will. You, as the testator, must also be at least 18 years old and of sound mind to be eligible to write the last will and testament in Virginia.

Step 2: Consult with state laws

Once it has been ascertained that the property is eligible, it is necessary to consult with the state laws as they will provide clarity as to how the items can be distributed. According to Virginia state law, a last will must follow certain formalities in order to be legally enforceable. A will is defined as “any testament, codicil, the exercise of a power of appointment by a will or writing in the nature of a will or any other testamentary disposition.” under Virginia laws (§ 64.2-100).

Step 3: Check all rules and requirements

States typically have codified their laws regarding wills in their constitutions or general statutes, which define a valid will and provide the rules for executing a will. These requirements often involve witnesses, seals, and other formalities as required by local laws. Virginia Code § 64.2-401 governs your eligibility in terms of age and capacity. Virginia Code § 64.2-401 states that a will in Virginia should address any property you owned at the time of writing the will.

Virginia state laws stipulate that the will should be in hard copy and not in any of the following formats: audio, video, or digital file. According to Virginia Code § 64.2-403, it can be handwritten even though it is not advocated.

Generally, under Virginia Code § 64.2-403, a will should be signed and dated by you, and at least two witnesses should witness the will. The signing should be done with all signatories present. Virginia Code § 64.2-405 states that “interested” parties—individuals who aim to inherit a portion of the property—can be witnesses.

However, it is always best to have all witnesses be “disinterested” parties. Holographic wills are permitted under Virginia Code § 64.2-403 and do not have to be witnessed. However, at least two people must attest that the will and the signature are authentic.

Step 4: Self-prove your will

Even though it is not required, self-proving is the final step before the court accepts and enforces the will as an official document. According to Virginia Code Virginia Code § 64.2-452, self-proving a will is done by visiting a notary public to have your affidavit of acknowledgment taken. You need to affirm under oath that you are the true owner of all property that is named in your will and that you have created your will unit to be valid under state laws.

Virginia Last Will and Testament Revocation Procedure

The procedure for voiding a will is called revocation. This could be done for a number of reasons, such as the property was not eligible to be included in the will, the will was improperly executed, or other improper provisions were made within. It is possible to revoke an existing will or codicil by tearing it up, cutting it off, cancelling it, lighting it on fire, obliterating it, or otherwise destroying it under Virginia Code § 64.2-410.

Any clause in your last will that automatically transfers property to your spouse or appoints them as your executor in Virginia is revoked by the state of Virginia upon divorce or annulment of your marriage. This is the case only if the will specifically states that its provisions are not to be affected by divorce or annulment. However, this stipulation of Virginia laws does not apply if you remarry your spouse under Virginia Code § 64.2-412.

Frequently Asked Questions

No, you do not require a lawyer to create a will in Virginia. However, if your property distribution process is complicated, hiring a lawyer will be more beneficial.

A will should name an executor, even if it is not required. It is advised that you designate a backup executor in case the primary executor is unable to carry out the will. If you do not designate an executor, your last will will be handled by a person the courts appoint.

No, it is not possible to make a digital or electronic will in Virginia. All last wills and testaments in Virginia must be in writing and signed. However, this may not be the case in some states. It is thus important to consult state laws.

You can find more info about making wills in the Code of Virginia, Title 64.2, “Wills, Trusts, and Fiduciaries,” Subtitle II “Wills and Decedents’ Estates,” Chapter 4 “Wills,” or on the website of the Office of the State Courts.

Yes, you can make changes to your will as long as these changes are still in line with Virginia state laws about making a will. This can be done through a codicil or amendment. This provision is helpful for testators who have had changes in their circumstances since writing their previous last will and testament but do not want to completely rewrite it.

Intestacy laws govern a situation where a person passes away without leaving a will (intestate). In instances where you have not left a will, your property is automatically given to your spouse and children. If the remaining children are not descendants of the surviving spouse, the spouse receives one-third of the estate, while the children receive two-thirds. If you die without a spouse and there are no children or parents, the property is then given to your siblings. If none of these people are alive and there is no next of kin, the property is transferred to more distant relatives, as defined by Virginia law.